Babajide Ogunlana, DPM, FACFAS

Hamidat Momoh, DPM

Joseph Olatunji, DPM, MBA

Symmetrical peripheral gangrene (SPG) is a rare, but life-threatening condition characterized by ischemic necrosis of the distal extremities, typically involving fingers, toes, or both, in the absence of large vessel obstruction. This condition is frequently associated with septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or prolonged vasopressor therapy.1 The pathophysiology of SPG involves microvascular thrombosis and failure of the distal circulation, which results in rapid tissue necrosis and gangrene.2

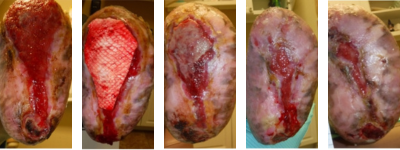

Figure 1. These images of the patient’s right foot show severe ischemic necrosis and forefoot gangrene. The foot exhibits extensive tissue necrosis, with blackened, mummified digits indicating dry gangrene, while the exposed ulcerated margins with erythema and drainage suggest superimposed infection and wet gangrene. In the dorsal view (left) and the anterior medial view (right), there is a clear demarcation between viable and non-viable tissue at the midfoot, with necrotic eschar formation over the toes and dorsal forefoot. The plantar view (center) reveals a large ulceration with macerated, necrotic tissue extending to the metatarsal heads, with potential deep tissue involvement. The presence of yellow slough and fibrinous exudate suggests chronic wound infection.

The incidence of SPG is increasing, especially in critical care where vasopressors are used to manage severe hypotension in patients with septic shock. Studies report that up to 70% of SPG cases result in amputation, and the condition carries a high mortality rate.3

First described by Hutchinson4 in 1891 as rare but severe gangrene of the distal extremities occurring with symmetrical distribution, the etiology of SPG is multifactorial and mostly diagnosed in the intensive care unit.5 While the exact pathogenesis of SPG is uncertain, a hypercoagulable vasospastic state leading to microcirculatory occlusion is known to cause symmetrical ischemic damage. It typically begins at the distal aspect of the limbs, sparing major vessels, and may progress proximally to involve the entire extremity.6

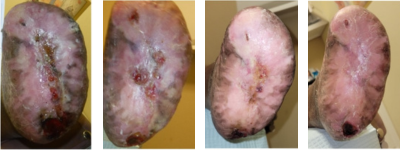

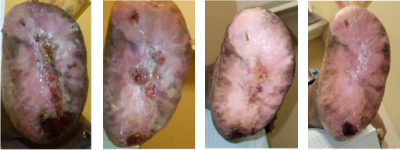

Figure 2. The above images of the patient’s left foot show extensive tissue n

ecrosis and gangrene with mummification of the toes and forefoot. There is black necrotic tissue present throughout the plantar (central) and forefoot (left and right) images, indicative of advanced ischemia. The affected areas demonstrate hard, desiccated tissue consistent with dry gangrene, while surrounding areas of erythema, sloughing, and purulence indicative of superimposed wet gangrene and infection. Demarcation is evident between viable and necrotic tissue, particularly notable at the midfoot and hindfoot regions.

Suspected early signs of SPG include marked coldness, pallor, cyanosis, or pain in an extremity, as the condition can progress rapidly to acrocyanosis and digital ischemia with intact distal pulses.7 Previous studies have listed a wide array of infective and non-infective etiological factors associated with SPG. Acute conditions include gram-positive and gram-negative septicemia, low cardiac output states, and, as previously mentioned, vasopressor use. This condition can develop at any age or in any sex.5 Chronic conditions associated with SPG include thrombocytopenia, polycythemia vera, Raynaud’s syndrome, diabetes, and small vessel obstruction.7

There is a consensus in the literature suggesting that early identification and treatment of the underlying cause are crucial for successful management. However, there are minimal evidence-based guidelines for SPG treatment, with a high risk of limb loss and amputation cited.6 This case illustrates a unique SPG presentation with a “slippers gangrene” appearance, successfully addressed through limb salvage interventions.

Case Report

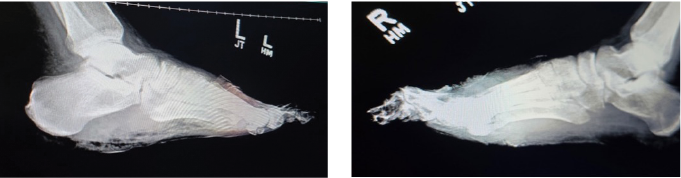

Figure 3. Lateral X-ray view of both left (left image) and right (right image) feet showing extensive bone destruction; including the toes and metatarsals secondary to osteomyelitis. There is soft tissue radiopacity overlying the forefoot on both sides, indicative of gangrenous tissue. One can also note gas within the soft tissues on both feet mostly at the plantar left foot.

Figure 3. Lateral X-ray view of both left (left image) and right (right image) feet showing extensive bone destruction; including the toes and metatarsals secondary to osteomyelitis. There is soft tissue radiopacity overlying the forefoot on both sides, indicative of gangrenous tissue. One can also note gas within the soft tissues on both feet mostly at the plantar left foot.

A 46-year-old African American male with a medical history including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, a prior acute cerebrovascular accident (CVA), acute renal injury, chronic cigarette use, aortic aneurysm with dissection, and tracheostomy tube placement, presented for urgent evaluation of worsening gangrenous changes to both forefeet. The symptoms, characterized by foul-smelling necrosis, had been ongoing for approximately 3 months.

Four months prior, the patient underwent emergent surgery for an aortic dissection from the ascending thoracic to the abdominal level, later complicated by multiple organ failure. Following this, he was placed on hemodialysis and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for treatment of urosepsis, where he also required intubation. Persistent hypotension further complicated his hospital course, requiring the initiation of vasopressor therapy to achieve and maintain adequate systolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure.

Over the course of several months, the patient experienced multiple hospital admissions. He was referred to the primary author’s office by his home health nurse due to progressively worsening, foul-smelling gangrenous necrosis of both feet. During his ICU stay, the patient initially developed dry gangrene, with plans to allow further demarcation and potentially monitor for autoamputation. However, after discharge, the patient did not adhere to management recommendations, and the dry gangrene progressed to wet gangrene.

On admission, the patient presented with fully demarcated wet gangrene involving both forefeet and fingers, raising concerns for infection. Physical examination revealed forefoot gangrene with associated fluctuance and crepitus (Figure 1) on the right foot and a “slippers” distribution necrotic appearance on the plantar surface of the left foot (Figure 2). Radiographic studies revealed evidence of bilateral acute osteomyelitis and cellulitis, with soft tissue gas present in both forefeet and scattered plantar soft tissue gas in the left midfoot and hindfoot, consistent with infection from a gas-forming organism (Figure 3).

Arterial ultrasound demonstrated moderate arterial disease without significant occlusion or stenosis, with normal arterial velocity and monophasic waveforms. Ankle-brachial indices (ABIs) were 0.74 on the right and 0.77 on the left, suggesting non-critical peripheral arterial disease. Profuse bleeding upon tourniquet deflation intraoperatively supported this finding. Microbiological cultures were positive for Citrobacter koseri and a non-Staphylococcus aureus staphylococcal species. The patient underwent a 6-week course of antibiotics. Originally, infection disease recommended vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole, switching to ceftriaxone and vancomycin after culture results. After discharge, the patient continued ceftriaxone via a PICC line. However, given the severity of the gangrene and infection, the patient underwent emergent surgical intervention, which included excisional debridement of the left foot down to bone, incision and drainage, and bilateral transmetatarsal amputations (TMA).

Details on the Surgical Intervention

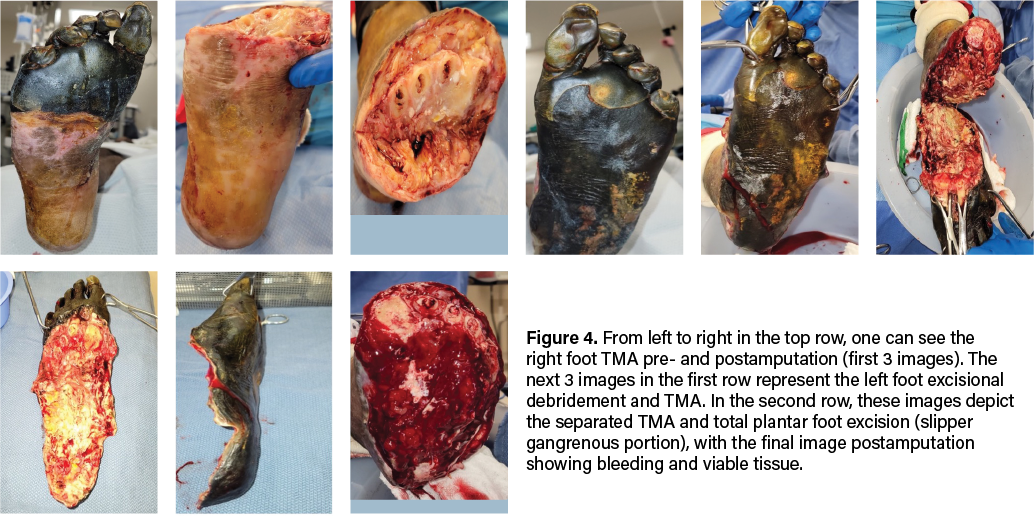

Due to evidence of adequate blood flow maintained at the midfoot and preserved sensory innervation to the feet, our team proceeded with emergent bilateral transmetatarsal amputation. A broad excisional resection of necrotic soft tissue using sharp and mechanical methods took place, followed by thorough mechanical irrigation with normal saline and antibiotic-impregnated solution. We noted significant bleeding during the case, necessitating the use of bilateral pneumatic ankle tourniquets for hemostatic control. To safely employ the tourniquet, we confirmed that demarcation was clearly significantly distal to its application, and there were no proximal concerns of warmth, edema, erythema, crepitus, or fluctuance. We reapproximated the right TMA stump site with retention sutures and packed the areas with antimicrobial-soaked gauze. We placed a silver active fluid management (AFM) dressing over the area, with a secondary, bulky sterile dressing placed for coverage (Figure 4). The left TMA, which involved more extensive necrosis of the plantar foot, required more extensive surgical intervention. We debrided the entire plantar aspect of the left foot, exposing the full soft tissue structure, including intrinsic muscles, ligaments, tendons, and bone. We applied a bulky non-adherent dressing, along with a silver-based active fluid management dressing for exudate control on this side. The area was further covered with a dry, sterile dressing for protection (Figure 4).

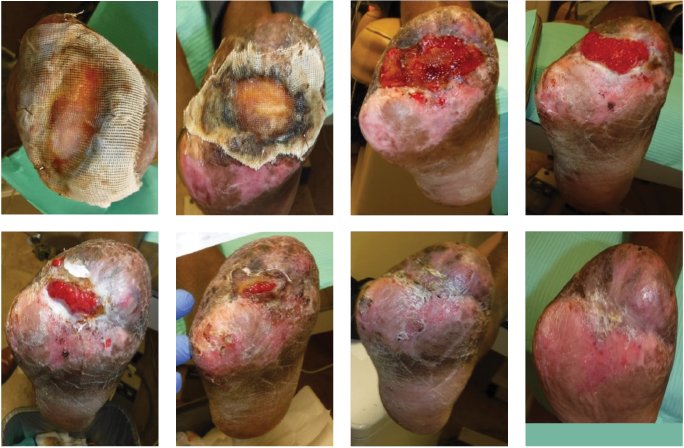

Figure 5. These photos show results 3 days postoperatively during a dressing change in the hospital. The 2 left-most images reflect the right foot and the 2 right images show the left foot.

The patient returned to the operating room one week later during his emergent hospital stay for further wound wash-out and wound bed preparation. We removed the retention sutures and prepared the wound bed until achieving adequate bleeding with sharp excisional debridement and a high-pressure hydrotherapy device. After thorough irrigation via pulse lavage with normal sterile saline, the right TMA stump wound measured 3.0cm x 8.2cm x 1.0cm. We packed this with 1 unit of 1000mg xenograft acellular matrix powder made into a paste and then covered with a sheet of 7cm x 10cm wound matrix xenograft secured with staples. The non-adherent dressing placed over the xenograft was also secured with staples and a bulky dressing.

Next, we mechanically debrided the left foot open plantar and TMA stump wounds to a bleeding base with multiple areas of bone exposure before copiously irrigating with normal sterile saline impregnated with antibiotics. Left TMA wound measured 18.0cm x 10.0 cm x 1.0cm, which we packed with 2 units of 1000mg xenograft matrix powder made into a paste and then covered with a 10cm x 15cm 3-layer wound matrix xenograft sheet secured with staples and sutures. The dressing also consisted of a non-adherent interface and bulky secondary layer.

There was excellent wound bed apposition and we decided against negative pressure wound therapy. We instructed the patient to only partially bear weight for transfers on the right, and for strict non-weight-bearing on the left. Hospital discharge then took place to home with a plan for outpatient clinic follow up weekly.

Postoperative Case Milestones

The treatment approach for SPG is multifaceted, emphasizing early identification, infection control, hemodynamic stabilization, and limb preservation where possible. This patient elected to pursue all attempts to limb salvage, hence TMA was chosen over major proximal amputation to retain maximal limb function and reduce morbidity. We used xenografts as temporary biological scaffolds to facilitate tissue regeneration and ideally reduce the need for further amputation.

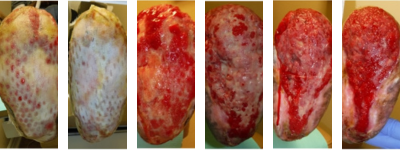

Figure 6. These photos show the right foot’s healing progression. The 2 top left images show the wound matrix xenograft stapled on the wound bed with a nonadherent dressing. The wound progressed well across the next 5 images, showing improved granulation, wound edges contracture and epithelization. The bottom right photo shows the wound completely healed.

Over the course of 12 weeks with weekly/biweekly outpatient clinic visits, and with serial use of AFM wound dressings for exudate management and judicious wound care, this patient eventually had complete wound healing of the right foot open TMA site. He did not require a return to the OR for that right foot. For the left foot TMA that required total plantar soft tissue coverage, this wound took more than a year to achieve full closure. His treatment plans involved serial AFM wound dressings for exudate management and strict non-weight-bearing with a rolling knee scooter. Adjuvant wound therapies including reapplication of advanced xenograft wound care products helped move the wound healing cascade forward when there was noticeable stagnation at 7 months postop. Serial debridements continued for both sites. The left plantar foot responded rapidly to the updated intervention with increasing epithelialization and wound edge contracture that progressed to near-complete epithelialization. A small opening on the plantar central left heel did require a partial calcanectomy.

As a result of the bilateral TMAs, the patient faces several physical, functional, and psychological challenges, significantly impacting mobility, independence, and overall quality of life. Some key difficulties the patient may encounter include mobility challenges, prosthetic/orthotic needs, secondary health complications (risk of further amputation, muscle atrophy, joint stiffness, phantom limb pain, and neuropathy), potential pressure injury if not using proper shoe gear and/or orthotics, psychological and emotional impact, and social and lifestyle impact. The team did refer the patient to an amputee support group to navigate some of these challenges.

In Summary

Symmetrical peripheral gangrene remains a challenging clinical entity with a high risk of amputation and mortality. In critically ill patients requiring vasopressors, vigilance for early signs of digital ischemia is crucial. This case underscores the importance of prompt infection control, vascular assessment, and aggressive surgical debridement to prevent disease progression and major limb loss. By employing a multidisciplinary approach incorporating transmetatarsal amputation, xenograft application, and wound bed optimization, the patient experienced successful limb salvage. Further research is necessary to establish standardized treatment protocols and improve long-term functional outcomes for patients with the complex pathology of symmetrical peripheral gangrene.

Editor’s Note: Please see below for additional online exclusive clinical photos.

Dr. Ogunlana practices at West Houston Foot & Ankle Center and is the Chief of Podiatry at Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital in Houston, Texas. He is a Fellow of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons.

Dr. Momoh is a resident at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Olatunji is a resident at St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester County, Massachusetts.

Figures 8A-D. From left to right, this series shows the left foot just after the partial calcanectomy (A), and a few weeks later after complete closure of the heel wound (B). Figures 8C and D are updates from February 2025.

Figures 7A-F. This sequence illustrates the progression of healing of the left foot TMA site. From left to right, figures A and B show the wound matrix xenograft staples onto the wound bed with a non-adherent dressing. Figures C-F show more progressive wound healing.

Figures 7G-K. Continuing the sequence from above, from left to right, figure G shows more healing progression, but this trajectory stalled. A fish skin graft was employed as shown in figure H, and figures I-K show subsequent wound contraction.

Figures 7G-K. Continuing the sequence from above, from left to right, figure G shows more healing progression, but this trajectory stalled. A fish skin graft was employed as shown in figure H, and figures I-K show subsequent wound contraction.

Figures 7L-O. Continuing the two sequences above, from left to right, one can see continued progress to 95% healing.

Figures 7L-O. Continuing the two sequences above, from left to right, one can see continued progress to 95% healing.

Figures 8A-D. From left to right, this series shows the left foot just after the partial calcanectomy (A), and a few weeks later after complete closure of the heel wound (B). Figures 8C and D are updates from February 2025.

Figures 8A-D. From left to right, this series shows the left foot just after the partial calcanectomy (A), and a few weeks later after complete closure of the heel wound (B). Figures 8C and D are updates from February 2025.

References

1. Khan F, Singh K, Arya S, Gupta N. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene: A prospective study of 12 cases. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;65:294-300.

2. Chua A, Lim C, Tan B. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene: A case report and review of the literature. J Crit Care Med. 2018;6(2):85–91.

3. Kwon JW, Hong MK, Park BY. Risk factors of vasopressor-induced symmetrical peripheral gangrene. Ann Plastic Surg. 2018;80(6):622-627.

4. Hutchinson J. On symmetrical gangrene of the extremities. Br Med J. 1891;2(1601):8–9.

5. Sharma A, Singh A, Gupta V. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene: A rare and devastating complication. Int J Crit Illness Injury Sci. 2017;7(2):123–126.

6. Frost B, Gloviczki P, Kalra M. Peripheral ischemic syndromes: Diagnosis and treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67(3):785–792.

7. Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene. Ind J Dermatol Venereol Leprosy. 2011;77(2):244–248.