Babajide Ogunlana, DPM, FACFAS

Hamidat Momoh, DPM

Joseph Olatunji, DPM, MBA

Symmetrical peripheral gangrene (SPG) is a rare, but life-threatening condition characterized by ischemic necrosis of the distal extremities, typically involving fingers, toes, or both, in the absence of large vessel obstruction. This condition is frequently associated with septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or prolonged vasopressor therapy.1 The pathophysiology of SPG involves microvascular thrombosis and failure of the distal circulation, which results in rapid tissue necrosis and gangrene.2

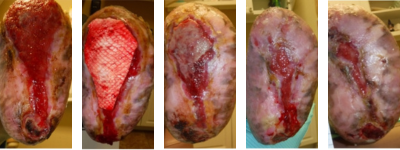

Figure 1. These images of the patient’s right foot show severe ischemic necrosis and forefoot gangrene. The foot exhibits extensive tissue necrosis, with blackened, mummified digits indicating dry gangrene, while the exposed ulcerated margins with erythema and drainage suggest superimposed infection and wet gangrene. In the dorsal view (left) and the anterior medial view (right), there is a clear demarcation between viable and non-viable tissue at the midfoot, with necrotic eschar formation over the toes and dorsal forefoot. The plantar view (center) reveals a large ulceration with macerated, necrotic tissue extending to the metatarsal heads, with potential deep tissue involvement. The presence of yellow slough and fibrinous exudate suggests chronic wound infection.

The incidence of SPG is increasing, especially in critical care where vasopressors are used to manage severe hypotension in patients with septic shock. Studies report that up to 70% of SPG cases result in amputation, and the condition carries a high mortality rate.3

First described by Hutchinson4 in 1891 as rare but severe gangrene of the distal extremities occurring with symmetrical distribution, the etiology of SPG is multifactorial and mostly diagnosed in the intensive care unit.5 While the exact pathogenesis of SPG is uncertain, a hypercoagulable vasospastic state leading to microcirculatory occlusion is known to cause symmetrical ischemic damage. It typically begins at the distal aspect of the limbs, sparing major vessels, and may progress proximally to involve the entire extremity.6

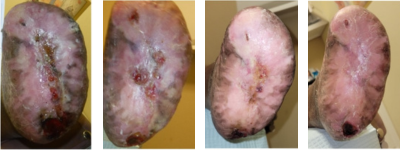

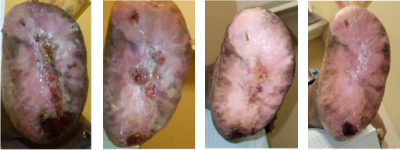

Figure 2. The above images of the patient’s left foot show extensive tissue n

ecrosis and gangrene with mummification of the toes and forefoot. There is black necrotic tissue present throughout the plantar (central) and forefoot (left and right) images, indicative of advanced ischemia. The affected areas demonstrate hard, desiccated tissue consistent with dry gangrene, while surrounding areas of erythema, sloughing, and purulence indicative of superimposed wet gangrene and infection. Demarcation is evident between viable and necrotic tissue, particularly notable at the midfoot and hindfoot regions.

Suspected early signs of SPG include marked coldness, pallor, cyanosis, or pain in an extremity, as the condition can progress rapidly to acrocyanosis and digital ischemia with intact distal pulses.7 Previous studies have listed a wide array of infective and non-infective etiological factors associated with SPG. Acute conditions include gram-positive and gram-negative septicemia, low cardiac output states, and, as previously mentioned, vasopressor use. This condition can develop at any age or in any sex.5 Chronic conditions associated with SPG include thrombocytopenia, polycythemia vera, Raynaud’s syndrome, diabetes, and small vessel obstruction.7

There is a consensus in the literature suggesting that early identification and treatment of the underlying cause are crucial for successful management. However, there are minimal evidence-based guidelines for SPG treatment, with a high risk of limb loss and amputation cited.6 This case illustrates a unique SPG presentation with a “slippers gangrene” appearance, successfully addressed through limb salvage interventions.

Case Report

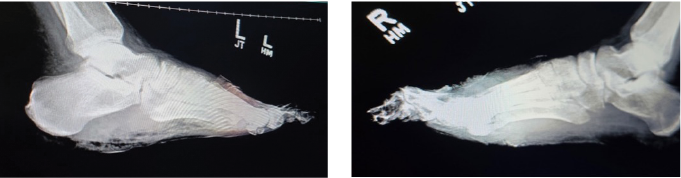

Figure 3. Lateral X-ray view of both left (left image) and right (right image) feet showing extensive bone destruction; including the toes and metatarsals secondary to osteomyelitis. There is soft tissue radiopacity overlying the forefoot on both sides, indicative of gangrenous tissue. One can also note gas within the soft tissues on both feet mostly at the plantar left foot.

Figure 3. Lateral X-ray view of both left (left image) and right (right image) feet showing extensive bone destruction; including the toes and metatarsals secondary to osteomyelitis. There is soft tissue radiopacity overlying the forefoot on both sides, indicative of gangrenous tissue. One can also note gas within the soft tissues on both feet mostly at the plantar left foot.

A 46-year-old African American male with a medical history including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, a prior acute cerebrovascular accident (CVA), acute renal injury, chronic cigarette use, aortic aneurysm with dissection, and tracheostomy tube placement, presented for urgent evaluation of worsening gangrenous changes to both forefeet. The symptoms, characterized by foul-smelling necrosis, had been ongoing for approximately 3 months.

Four months prior, the patient underwent emergent surgery for an aortic dissection from the ascending thoracic to the abdominal level, later complicated by multiple organ failure. Following this, he was placed on hemodialysis and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for treatment of urosepsis, where he also required intubation. Persistent hypotension further complicated his hospital course, requiring the initiation of vasopressor therapy to achieve and maintain adequate systolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure.

Over the course of several months, the patient experienced multiple hospital admissions. He was referred to the primary author’s office by his home health nurse due to progressively worsening, foul-smelling gangrenous necrosis of both feet. During his ICU stay, the patient initially developed dry gangrene, with plans to allow further demarcation and potentially monitor for autoamputation. However, after discharge, the patient did not adhere to management recommendations, and the dry gangrene progressed to wet gangrene.

On admission, the patient presented with fully demarcated wet gangrene involving both forefeet and fingers, raising concerns for infection. Physical examination revealed forefoot gangrene with associated fluctuance and crepitus (Figure 1) on the right foot and a “slippers” distribution necrotic appearance on the plantar surface of the left foot (Figure 2). Radiographic studies revealed evidence of bilateral acute osteomyelitis and cellulitis, with soft tissue gas present in both forefeet and scattered plantar soft tissue gas in the left midfoot and hindfoot, consistent with infection from a gas-forming organism (Figure 3).

Arterial ultrasound demonstrated moderate arterial disease without significant occlusion or stenosis, with normal arterial velocity and monophasic waveforms. Ankle-brachial indices (ABIs) were 0.74 on the right and 0.77 on the left, suggesting non-critical peripheral arterial disease. Profuse bleeding upon tourniquet deflation intraoperatively supported this finding. Microbiological cultures were positive for Citrobacter koseri and a non-Staphylococcus aureus staphylococcal species. The patient underwent a 6-week course of antibiotics. Originally, infection disease recommended vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole, switching to ceftriaxone and vancomycin after culture results. After discharge, the patient continued ceftriaxone via a PICC line. However, given the severity of the gangrene and infection, the patient underwent emergent surgical intervention, which included excisional debridement of the left foot down to bone, incision and drainage, and bilateral transmetatarsal amputations (TMA).

Details on the Surgical Intervention

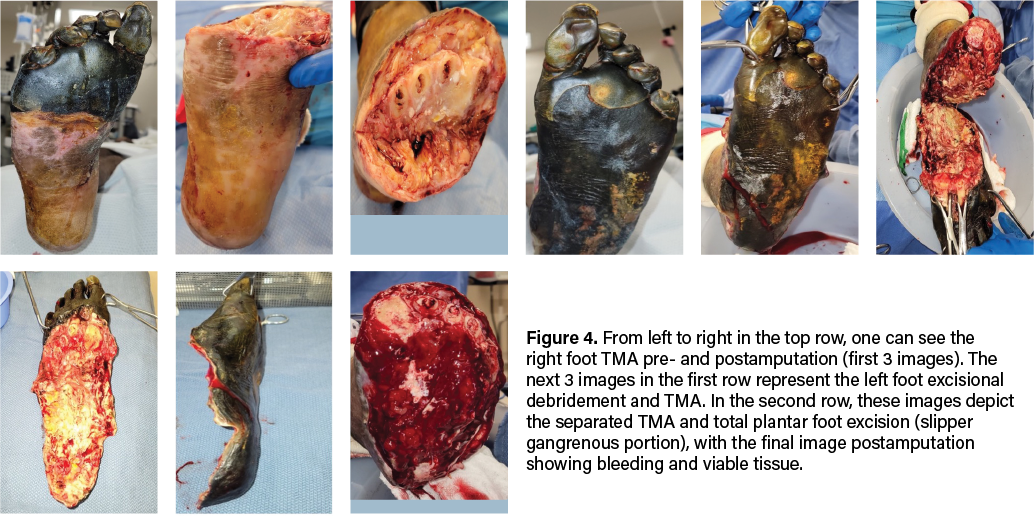

Due to evidence of adequate blood flow maintained at the midfoot and preserved sensory innervation to the feet, our team proceeded with emergent bilateral transmetatarsal amputation. A broad excisional resection of necrotic soft tissue using sharp and mechanical methods took place, followed by thorough mechanical irrigation with normal saline and antibiotic-impregnated solution. We noted significant bleeding during the case, necessitating the use of bilateral pneumatic ankle tourniquets for hemostatic control. To safely employ the tourniquet, we confirmed that demarcation was clearly significantly distal to its application, and there were no proximal concerns of warmth, edema, erythema, crepitus, or fluctuance. We reapproximated the right TMA stump site with retention sutures and packed the areas with antimicrobial-soaked gauze. We placed a silver active fluid management (AFM) dressing over the area, with a secondary, bulky sterile dressing placed for coverage (Figure 4). The left TMA, which involved more extensive necrosis of the plantar foot, required more extensive surgical intervention. We debrided the entire plantar aspect of the left foot, exposing the full soft tissue structure, including intrinsic muscles, ligaments, tendons, and bone. We applied a bulky non-adherent dressing, along with a silver-based active fluid management dressing for exudate control on this side. The area was further covered with a dry, sterile dressing for protection (Figure 4).

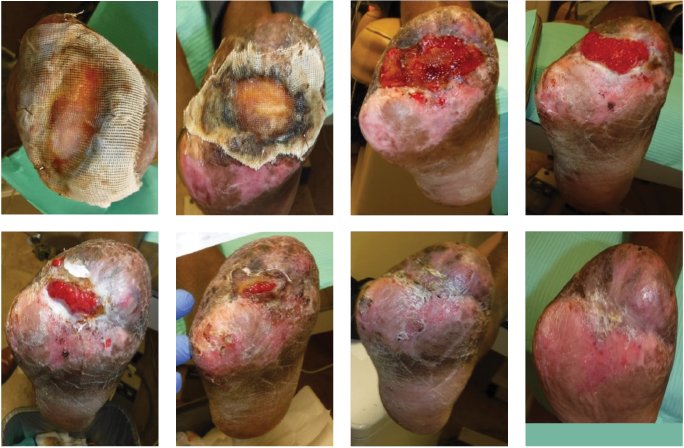

Figure 5. These photos show results 3 days postoperatively during a dressing change in the hospital. The 2 left-most images reflect the right foot and the 2 right images show the left foot.

The patient returned to the operating room one week later during his emergent hospital stay for further wound wash-out and wound bed preparation. We removed the retention sutures and prepared the wound bed until achieving adequate bleeding with sharp excisional debridement and a high-pressure hydrotherapy device. After thorough irrigation via pulse lavage with normal sterile saline, the right TMA stump wound measured 3.0cm x 8.2cm x 1.0cm. We packed this with 1 unit of 1000mg xenograft acellular matrix powder made into a paste and then covered with a sheet of 7cm x 10cm wound matrix xenograft secured with staples. The non-adherent dressing placed over the xenograft was also secured with staples and a bulky dressing.

Next, we mechanically debrided the left foot open plantar and TMA stump wounds to a bleeding base with multiple areas of bone exposure before copiously irrigating with normal sterile saline impregnated with antibiotics. Left TMA wound measured 18.0cm x 10.0 cm x 1.0cm, which we packed with 2 units of 1000mg xenograft matrix powder made into a paste and then covered with a 10cm x 15cm 3-layer wound matrix xenograft sheet secured with staples and sutures. The dressing also consisted of a non-adherent interface and bulky secondary layer.

There was excellent wound bed apposition and we decided against negative pressure wound therapy. We instructed the patient to only partially bear weight for transfers on the right, and for strict non-weight-bearing on the left. Hospital discharge then took place to home with a plan for outpatient clinic follow up weekly.

Postoperative Case Milestones

The treatment approach for SPG is multifaceted, emphasizing early identification, infection control, hemodynamic stabilization, and limb preservation where possible. This patient elected to pursue all attempts to limb salvage, hence TMA was chosen over major proximal amputation to retain maximal limb function and reduce morbidity. We used xenografts as temporary biological scaffolds to facilitate tissue regeneration and ideally reduce the need for further amputation.

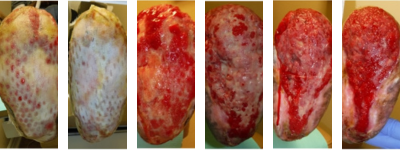

Figure 6. These photos show the right foot’s healing progression. The 2 top left images show the wound matrix xenograft stapled on the wound bed with a nonadherent dressing. The wound progressed well across the next 5 images, showing improved granulation, wound edges contracture and epithelization. The bottom right photo shows the wound completely healed.

Over the course of 12 weeks with weekly/biweekly outpatient clinic visits, and with serial use of AFM wound dressings for exudate management and judicious wound care, this patient eventually had complete wound healing of the right foot open TMA site. He did not require a return to the OR for that right foot. For the left foot TMA that required total plantar soft tissue coverage, this wound took more than a year to achieve full closure. His treatment plans involved serial AFM wound dressings for exudate management and strict non-weight-bearing with a rolling knee scooter. Adjuvant wound therapies including reapplication of advanced xenograft wound care products helped move the wound healing cascade forward when there was noticeable stagnation at 7 months postop. Serial debridements continued for both sites. The left plantar foot responded rapidly to the updated intervention with increasing epithelialization and wound edge contracture that progressed to near-complete epithelialization. A small opening on the plantar central left heel did require a partial calcanectomy.

As a result of the bilateral TMAs, the patient faces several physical, functional, and psychological challenges, significantly impacting mobility, independence, and overall quality of life. Some key difficulties the patient may encounter include mobility challenges, prosthetic/orthotic needs, secondary health complications (risk of further amputation, muscle atrophy, joint stiffness, phantom limb pain, and neuropathy), potential pressure injury if not using proper shoe gear and/or orthotics, psychological and emotional impact, and social and lifestyle impact. The team did refer the patient to an amputee support group to navigate some of these challenges.

In Summary

Symmetrical peripheral gangrene remains a challenging clinical entity with a high risk of amputation and mortality. In critically ill patients requiring vasopressors, vigilance for early signs of digital ischemia is crucial. This case underscores the importance of prompt infection control, vascular assessment, and aggressive surgical debridement to prevent disease progression and major limb loss. By employing a multidisciplinary approach incorporating transmetatarsal amputation, xenograft application, and wound bed optimization, the patient experienced successful limb salvage. Further research is necessary to establish standardized treatment protocols and improve long-term functional outcomes for patients with the complex pathology of symmetrical peripheral gangrene.

Editor’s Note: Please see below for additional online exclusive clinical photos.

Dr. Ogunlana practices at West Houston Foot & Ankle Center and is the Chief of Podiatry at Memorial Hermann Southwest Hospital in Houston, Texas. He is a Fellow of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons.

Dr. Momoh is a resident at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Olatunji is a resident at St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester County, Massachusetts.

Figures 8A-D. From left to right, this series shows the left foot just after the partial calcanectomy (A), and a few weeks later after complete closure of the heel wound (B). Figures 8C and D are updates from February 2025.

Figures 7A-F. This sequence illustrates the progression of healing of the left foot TMA site. From left to right, figures A and B show the wound matrix xenograft staples onto the wound bed with a non-adherent dressing. Figures C-F show more progressive wound healing.

Figures 7G-K. Continuing the sequence from above, from left to right, figure G shows more healing progression, but this trajectory stalled. A fish skin graft was employed as shown in figure H, and figures I-K show subsequent wound contraction.

Figures 7G-K. Continuing the sequence from above, from left to right, figure G shows more healing progression, but this trajectory stalled. A fish skin graft was employed as shown in figure H, and figures I-K show subsequent wound contraction.

Figures 7L-O. Continuing the two sequences above, from left to right, one can see continued progress to 95% healing.

Figures 7L-O. Continuing the two sequences above, from left to right, one can see continued progress to 95% healing.

Figures 8A-D. From left to right, this series shows the left foot just after the partial calcanectomy (A), and a few weeks later after complete closure of the heel wound (B). Figures 8C and D are updates from February 2025.

Figures 8A-D. From left to right, this series shows the left foot just after the partial calcanectomy (A), and a few weeks later after complete closure of the heel wound (B). Figures 8C and D are updates from February 2025.

References

1. Khan F, Singh K, Arya S, Gupta N. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene: A prospective study of 12 cases. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;65:294-300.

2. Chua A, Lim C, Tan B. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene: A case report and review of the literature. J Crit Care Med. 2018;6(2):85–91.

3. Kwon JW, Hong MK, Park BY. Risk factors of vasopressor-induced symmetrical peripheral gangrene. Ann Plastic Surg. 2018;80(6):622-627.

4. Hutchinson J. On symmetrical gangrene of the extremities. Br Med J. 1891;2(1601):8–9.

5. Sharma A, Singh A, Gupta V. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene: A rare and devastating complication. Int J Crit Illness Injury Sci. 2017;7(2):123–126.

6. Frost B, Gloviczki P, Kalra M. Peripheral ischemic syndromes: Diagnosis and treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67(3):785–792.

7. Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene. Ind J Dermatol Venereol Leprosy. 2011;77(2):244–248.

Podiatrist Dr. Babajide Ogunlana talks about foot care on the daily talk show program, SoulFood Health Education on SmoothFM 98.1 FM Lagos, Nigeria. Listen to how you care for your feet, and identify certain foot and ankle conditions like Athlete foot and Achilles tendon. Get simple exercises on how to strengthen your foot and ankle that you can do at home or any space.

Fashionable shoes are seldom sensible. However, some trends are better for feet than others. While some might assume the current look of wearing trainers with thick, chunky soles would be good for your feet – think of all that extra cushioning – leading podiatrists say otherwise.

Part of the popularity of these shoes might have come from the fact they are much more comfortable than other fashion shoes for women, particularly high heels. However, they come with their own risks. In particular, the weight of the trainers is an issue that could lead to health problems down the line.

In the midst of the ongoing opioid crisis, this author emphasizes obtaining thorough patient and medication histories, strategies for minimizing opioid use, and maximizing the benefits of non-opioid alternatives.

Patients often present for treatment aimed at alleviating pain and improving their quality of life. As physicians in the age of the opioid crisis, we are torn between acting as responsible stewards of opioid treatment while providing enough medication to alleviate pain, which is often surgically-induced. As we try to understand and follow evolving guidelines, policies and rules on pain management, we need to broaden our understanding and, most importantly, be open to utilizing available alternatives.

While there are many resources regarding pain and opioids, there is not much evidence-based data for physicians to follow. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), state departments of public health and human services (DPHHS) programs, health insurance carriers, big box pharmacies and hospitals all have their own programs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, however, provides some clinical practice guidelines, including a mobile app.1

Understanding The Importance Of Patient Communication In Pain Management

Informing a patient of the risks of addiction and use of opioids is just as important as informing them about the risks and complications of a particular procedure. Start the conversation about post-operative pain control prior to scheduling surgery. Be realistic about surgically-induced pain and the modalities available to decrease this pain. Increase your patients’ understanding that medication will decrease but not eliminate their pain.

Have a conversation about which medications you will prescribe, the limited number of pills you will provide and/or the number of planned refills, even if it is zero. Provide supporting references to hospital, pharmacy or insurance policies regarding opioid-naïve patients and chronically opioid-exposed patients. Be prepared to treat pain in patients recovering from addiction as well, which requires additional consideration.

Are our psychosocial histories adequate? Do we know if our patients have a history of previous chronic opioid use or addiction, psychological or sexual abuse, anxiety, depression or bipolar disease or tobacco, alcohol or illicit drug abuse? Are they facing socioeconomic challenges?

These are all risk factors for long term post-operative opioid use, chronic opioid dependence and future addiction. Limiting and/or eliminating opioid use in this population may prevent future addiction.2

During the postoperative period, keep an open dialogue with patients. These phone calls or office visits should serve as a reminder regarding the healing process and the progression of post-operative pain levels. Take this opportunity to remind them about non-opioid alternative pain management techniques, such as those recommended by the American Pain Society.3

What You Should Know About A Multifaceted Approach To Non-Opioid Surgical Pain Management

Multi-modal pain management is optimal for all pain control, not just surgical pain. Providers have many options from which to choose.

Local anesthetics. This begins with adequate pedal and regional blocks (with or without ultrasound guidance). Neuraxial anesthesia and peripheral nerve blocks are excellent for pain prevention and relief. Despite the use of general anesthesia, local infiltration with pedal and regional blocks using local anesthetics are still beneficial prior to any incision.4

Local infiltration of Exparel® (Pacira BioSciences), a newly marketed encapsulated liposomal bupivacaine preparation, can be an excellent postoperative choice. This non-opioid agent can provide 48 to 72 hours of anesthesia. It is important to note that Exparel is contraindicated for intra-articular use.5 The FDA may be reviewing additional long-acting injectable local anesthetic preparations in the next few years.

Gabapentinoids. When employing gabapentin or pregabalin (Lyrica®, Pfizer), it is best to administer these medications at least two hours prior to surgery. These drugs shut down excitatory neurotransmitters and decrease upregulation of the central nervous system. However, these drugs do depress the respiratory system so one should exercise caution with these medications for patients who are at high risk for respiratory depression.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen. Whether one opts for IV or oral administration, these drugs do have a place in perioperative pain management. These medications decrease the release of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and peripheral pain mediators.

In a presentation at a symposium on postoperative pain, David L. Nelson MD, an orthopedic hand surgeon, provided an excellent guideline for perioperative use of multimodal pain prevention and management in the orthopedic patient.6 His protocol includes the following steps:

1. Discuss the issue of pain with the patient before surgery.

2. Utilize a NSAID (naproxen sodium or celecoxib) and long-acting acetaminophen the morning of surgery.

3. Use lidocaine in the incisional area preoperatively.

4. Ensure careful tissue handling.

5. Utilize 0.5% marcaine with epinephrine in the surgical site postoperatively.

6. Have the patient use a NSAID (naproxen sodium or celecoxib) and long-acting acetaminophen after surgery.

7. Phone the patient on the first postoperative day to reinforce the pain management protocol.

8. Ask patients about their postoperative pain.

Ketamine. This is an effective drug agonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and has become an adjunct intraoperatively. It continues to be more popular in the treatment of chronic opioid-dependent patients and those recovering from addiction.7 I recommend having a conversation with your local anesthesiologist about the use of this drug in your operative patients.

Alpha-2 agonists. Clonidine and dexmedetomidine hydrochloride (Precedex™, Pfizer) can be useful agents. These drugs can provide sedation, decreased anxiety, sympatholytic effects and analgesia. However, it is important to be aware that they can cause bradycardia and hypotension due to their effect on blood flow.

Non-Opioid Pain Control Options In The Non-Surgical Patient

Podiatrists also see a significant number of non-surgical patients that need to manage pain. Although the approaches and options may differ, there are multiple diverse choices that one can employ.

NSAIDs and acetaminophen. In my experience, these are among the main treatment options that most patients and physicians use to manage pain. In a recent lecture at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, Brian Hainline, MD, maintained that acetaminophen in particular is “vastly, vastly under-prescribed” for acute pain.8 Dr. Hainline noted that acetaminophen and appropriate use of an anti-inflammatory drug can actually augment each other. For athletes who have pain but want to compete the same day, if they don’t have any biomechanical limitations, acetaminophen is a viable option for pain management, according to Dr. Hainline, the Chief Medical Officer of the National Collegiate Athletic Association.8

Massage and soaking. Massage for 10 to 20 minutes can be beneficial for pain management, in my experience. An adjunctive option, massage may decrease pain and muscular tension, and one can supplement this with traditional pain-relieving topical preparations such as IcyHot®. Essential oils such as peppermint oil, lavender oil, black pepper oil, juniper oil, arnica oil and rosemary oil have also been more in vogue recently.9

Soaking the feet, lower extremities and body can have a relaxing effect, which relieves anxiety, and subsequently decreases pain levels in patients. Traditional soaking preparations have Epsom salt bases that reportedly provide magnesium through the skin, relieving muscular aches.10 Other alternatives include adding one half-cup of apple cider vinegar and one half-cup of Epsom salt to one quart of warm water. Magnesium deficiency is often found in patients with fibromyalgia, migraine and chronic muscle spasms.10

Sleep. Sleep disturbances worsen chronic pain and musculoskeletal diseases.11 Establishing a regular sleep pattern should be a top priority. For those having trouble sleeping due to pain, one may initially consider over-the-counter preparations, such as diphenhydramine-based preparations or melatonin. Physicians must never overlook sleep apnea and refer patients to sleep medicine specialists when necessary for treatment.11

Could Complementary Therapies And Diet Changes Have An Impact In Pain Reduction?

Complementary modalities can have a place in providing pain control and improving health. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Health can provide a wealth of information on this topic.12

Herbs and supplements. Turmeric is the most common herbal preparation people use to decrease inflammation.12 Researchers have suggested that eight to 12 weeks of turmeric extract 1,000 mg/day can reduce arthritic symptoms similar to the improvement patients may get with naproxen or diclofenac.13

Glucosamine chondroitin, according to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, is a safe and well tolerated supplement.14 Glucosamine chondroitin can provide relief from osteoarthritic symptoms when patients take it in recommended doses. However, physicians must remember that glucosamine chondroitin may interfere with warfarin and high doses of the medication may harm the kidneys, and interfere with glucose metabolism in those with diabetes.14

Anti-inflammatory diets. Getting any patient to change his or her diet can be extremely difficult. That said, diet modification can be a great addition to pain treatment and when it is successful, patients have expressed remarkable improvement in my clinical experience. Increased body mass index (BMI) is associated with increased pain, anxiety, fatigue and decreased activity, and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia.15

Patients with pain should avoid inflammatory foods such as refined grains (rice, white potatoes, pasta, and bread), deep fried foods, pre-packaged/fast foods, corn oil, dairy products, soda, trans fats, margarines and grain-fed meats. Conversely, one should consume anti-inflammatory foods such as raw nuts, sweet potatoes, root vegetables, green tea, wild caught fish, bone broths, eggs, dark chocolate, garlic olive oil, coconut oil, avocado, green leafy vegetables and berries regularly. These changes may improve BMI and be beneficial to the patient’s general health.15

What About The Roles Of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy And Relaxation Techniques?

Cognitive behavioral therapy and relaxation techniques. Cognitive behavioral therapy addresses some of the underlying issues, such as anxiety, fear, distress and avoidance, that make the perception of physical pain worse.16 Counseling provides the opportunity for support groups along with the introduction to self-management techniques for coping and relaxation.16

Periodic deep breathing and meditation can be helpful. Movement with meditation such as yoga and tai chi can be extremely beneficial in increasing relaxation with range of motion, stretching and toning exercises.16

Where Do Opioids Fit In A Multimodal Approach To Pain?

While there a variety of non-opioid options for pain management, opioids still may play a role in treatment algorithms. However, it is essential to ensure proper opioid stewardship.

In the area of perioperative pain control, I follow the motto “give patients only what they need.”

Why should we limit the number of opioids we prescribe?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that 20 percent of patients who are still taking opioids at 10 days postoperatively will continue to take opioids a year later. That figure rises to 40 percent for those on opioids at 30 days post-op.17 The CDC also notes that 32 percent of opioid addicts report their first exposure from someone else’s medical supply.4

Despite these alarming numbers, in a recent survey in Outpatient Surgery magazine, 44 percent of physicians noted they do not decrease the number of opioids they prescribe due to the convenience of fewer postoperative phone calls from patients.4

There are relatively recent CDC guidelines on chronic pain management.1 Overall, they serve as excellent reminder of the risks of combining medications as well as reinforcing that we should provide the lowest amount of opioid medication for the shortest time possible. However, what is the magic number or should there be one?

Many resources recommend three days of opioid medication with reassessment at that time.1,18

Published limits for an initial prescription in an opioid-naïve patient range from five to seven days of opioids and a maximum of 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) or less per day.18 No longer should physicians provide prescriptions for 35, 40, 50 or 60 pills.

Some limits on opioid prescriptions are written into state laws. In the state of Michigan, the Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network (OPEN) has been in place since 2016 with the support of the Michigan Department of Public Health and Human Services, Blue Cross/Blue Shield and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at the University of Michigan. This network has released evidence-based opioid prescription guidelines for 25 different surgeries.19 However, we should remember that we may need to be flexible based on a patient’s individual needs.

We won’t address the emerging role of cannabinoids in pain control in this article. We can’t list all of the alternative treatments or modalities available. However, it is important for the provider to realize that we don’t understand exactly how much pain experienced by an individual is due to structural/physical changes versus the body’s response to psychosocial stressors.

In Conclusion

As prescribers, it is our responsibility to understand a variety of ways to help our patients control pain adequately and safely. In an age when opioid addiction continues to grow, familiarity and comfort with alternative options to supplement or replace opioids may help improve outcomes and avoid risk.

Dr. Painter is the Immediate Past President for the American Board of Podiatric Medicine, and is in practice in Great Falls, Montana. She is an Adjunct Professor at the Pacific Northwest College of Osteopathic Medicine and an Adjunct Professor of Podiatry at the Idaho College of Osteopathic Medicine.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. Available at: https: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html . Published August 28, 2019. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- PainEDU. Improving pain treatment through education. Available at: www.painedu.org . Accessed April 15, 2020.

- American Academy of Pain Medicine. AAPM pain treatment guidelines. https://drogunlana.com/2020/05/05/aspirin-for-prevention/ . Accessed May 5, 2020.

- Cook D. A nation in crisis. Outpatient Surgery. 2020:10-16. Available at: http://magazine.outpatientsurgery.net/i/1198986-special-edition-opioids-january-2020-subscribe-to-outpatient-surgery-magazine/0 . Published January 2020. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- Pacira BioSciences. Exparel website. Available at: www.exparel.com . Accessed April 15, 2020.

- Nelson DL. Managing surgical pain in the opioid epidemic era. Symposium presented at: 2014 American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Annual Meeting. March 11-15, 2014. New Orleans, La. Available at: http://www.davidlnelson.md/PainSymposium2014AAOS.htm Accessed April 16, 2020.

- Ye F, Wu Y, Zhou C. Effect of intravenous ketamine for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(51):e9147.

- Hainline B. Pain management in athletes. Lecture presented at: American Academy of Pain Medicine Annual Meeting. February 28, 2020. Vancouver, BC.

- Sparks D. Home remedies: what are the benefits of aromatherapy? Mayo Clinic News Network website. Available at: https://newsnetwork.mayoclinic.org/discussion/home-remedies-what-are-the-benefits-of-aromatherapy/ . Published May 8, 2019. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Why take an Epsom salt bath? WebMD. Available at: https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/epsom-salt-bath#1. Reviewed July 20, 2017. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539-1552.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website. Available at: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Daily JW, Yang M, Park S. Efficacy of turmeric extracts and curcumin for alleviating the symptoms of joint arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Med Food. 2016;19(8):717-729.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Glucosamine and chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Available at: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/glucosamine-and-chondroitin-for-osteoarthritis. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- Brusca SB, Abramson SB, Scher JU. Microbiome and mucosal inflammation as extra-articular triggers for rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26(1):101-107.

- Schubiner H. Mindfulness, CBT and ACT for chronic pain. Psychology Today. Available at: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/unlearn-your-pain/201412/mindfulness-cbt-and-act-chronic-pain . Published December 8, 2014. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- Hoots BE, Xu L, Kariisa M, et al. 2018 annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf . Accessed April 21, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf . Accessed April 21, 2020.

- Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network. Prescribing recommendations. Available at: https://michigan-open.org/prescribing-recommendations/ . Updated February 25, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2020.